I’m seeing more and more financial products being sold primarily based on their tax benefits, which always makes me a little nervous.

Sure, nobody likes to pay taxes, and you should minimize them when you can.

But for my lawyer clients – telling them they can save on taxes through a particular investment approach – is a very effective means to get your financial salesman foot in the door.

One financial product in particular sold this way is something called “Direct Indexing”, or “Personalized Indexing”, and while it goes by a number of names, I think the slickest is probably “Tax Smart” investing.

Tax Smart Investing… Oh, that’s a clever title for sure. I mean, who doesn’t want to be SMART (we all do!) about TAXES (which we all hate, right?)

I don’t think it’s nearly as bad as whole life insurance – which is also leans heavily on the tax angle to be sold – but there are some analogies worth highlighting. It’s quite a complex financial product, and I doubt that those who buy into this are fully informed on the pros (which is what it’s sold on) and its downsides (which there are quite a few).

To understand what this financial product is – and why I’m not a big fan – allow me to tell you a story of Wall Street, and how we got to “Tax Smart” investing.

The Evolution of Wall Street (Part 1)

The Stockbroker

Many, many years ago, the way Wall Street worked was you had a guy (they were all guys) who was a “stockbroker.”

The stockbroker would call around, get clients, and convince them to buy stock in IBM, GE, General Motors, or US Steel (these were the Apples, Teslas, and NVIDIA of their day).

One of the things that made the stockbroker happiest was to make money. For himself. And the way he made money was to have his clients trade because he earned a commission with each trade. Trade. Trade. Trade. Trade enough, and the stockbroker had enough money to go on that vacation or buy that new car. (If you want to understand Wall Street – or any other business for that matter – follow the money, right?)

But this story isn’t about the ethics of the stockbroker, it’s about the merits of whatever investment the stockbroker was selling. And in that, sometimes the stock investment was good, and sometimes it was not.

But one thing the investment always was, was concentrated.

The stockbroker sold you one stock, or a couple, or a few. Maybe even a dozen or more. But however many stocks the stockbroker sold you, you – the investor – would own a very few number of individual stocks out of all those that were available to purchase.

The Evolution of Wall Street (Part 2)

Mutual Funds

Over time, based on both experience and on academic research, people realized that it was better to own more stocks rather than fewer.

Some stocks would go up, others would go down, but what you were focused on was the aggregate of all of your positions. On how your overall stock portfolio was doing. And so, the mutual fund was born. Way back in 1924, in fact.

Smart investment managers would be paid a management fee to create a portfolio of individual stocks.

Years passed, and people began to notice something. They noticed that after accounting for the managers’ fees, their returns were actually not that great.

It turns out that picking stocks was very hard. And while sometimes some managers did well, on average – after taking into account the cost of paying these managers to pick stocks – most did not do so well.

The Evolution of Wall Street (Part 3)

The Arrival of The Index Fund (Nirvana!)

One day, a very smart and good man working on Wall Street – named John Bogle – had both the insight and ability to launch a whole new way of investing.

While John Bogle’s early days on Wall Street were spent as an active manager of mutual funds, he came to see that the best way to invest was by simply owning all the stocks you possibly could for as low a price as possible. And so, Vanguard was born.

While there’s a lot more to the story, this really was (and is) Investing Nirvana. I don’t think “Investing Nirvana” is much of an overstatement. I cannot think of a greater pinnacle of efficiency in the capital markets than this.

Take, for example, Vanguard’s ETF that goes by the ticker “VTI”. That’s the “Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF.” If you were to buy a share, you know what you get with this? An investment which in turn holds stock in just about every major publicly traded company in the United States: a portfolio of over 3,600 stocks!

Can you guess what the fee is for this investing Nirvana? 0.03%. That’s right. For every $100 invested in VTI, you’re paying 3 cents in fees. THREE. CENTS.

So, the investor has reached Nirvana, we’re done, right? All investors went to live Happily Ever After, right?

Not quite.

(De)volution on Wall Street? (Part 4)

…Direct Indexing

Well, with the growth of index funds and their astonishingly small fees, the guys who used to be stockbrokers aren’t making nearly as much money as they used to. So, the former stockbrokers got together with the guys who sell whole life insurance, and they think of stuff to sell, and how to sell it. (1)

And so, Direct Indexing was born.

Or, for those firms with slick marketers who have to come up with clever product names designed to get your tax-smart juices flowing, we’ll call it “Tax Smart Investing.”

What could this improvement on Nirvana be? Well, let me first give you “the pitch”

The (Unofficial) Direct Indexing Selling Script

Sure, Mr. Smart Lawyer… investing in a boring index fund is GREAT. I mean…. For the little guy, right?

But you? YOU? Mr. Lawyer, you are SMART, and YOU pay a lot of taxes because you are so successful. You don’t like taxes, do you?

Good news! We’re figured out a way for you to pay LESS in taxes.

It’s based on something called “Tax Loss Harvesting.” (2)

Here’s how it works: when an investment goes down in value below your purchase price (ouch!) – there is a silver lining. Just sell it and realize the loss for tax purposes! You get a “capital loss,” and you can use it to shelter capital gains.

Don’t have any capital gains you say? No problem! You can keep that capital loss and carry it with you as long as you want, until the day you need it to offset your FUTURE capital gains. (2) Cool, right?

Ok, here’s the catch. You don’t really want to sell that stock you have when it goes down, right? I mean, we wanted that investment, and if we liked it at $100 (before the price fell), shouldn’t we LOVE it at $80 (after the market took a dip)?

So, if we sell IBM (for example), shouldn’t we just buy it right back after we recognize that capital loss for tax purposes?

Not so fast! The pesky IRS has this annoying rule. It’s called the Wash Sale Rule. And it says that if we buy IBM stock back within 30 days of selling it in which we recognize a tax loss.. a yellow flag is thrown in the air, whistles blow, and there’s a foul called on that play. The penalty is: no tax loss is allowed.

But here’s the magic of our strategy, because we are so Tax Smart:

Instead of buying back the stock we just sold, we buy something back that is not exactly the same stock, but something kinda like it!

If we just sold IBM stock, and can’t buy it right back, how ’bout we buy XEROX stock instead??!?

I mean, XEROX and IBM are pretty similar, right?!? If you liked IBM stock, you’ll LOVE XEROX stock.

And yeah, yeah, we get you want to basically own all the stocks in the S&P 500 (just like the waiters and ditch diggers), but how about we just own 100 or 150 stocks. That’s probably enough, right? (500 is a LOT of stocks, who needs that many anyway??)

Based on our super Tax Smart mathematical models, our portfolio of just 100 or 150 stocks SHOULD act just (kinda) like the S&P 500.

I mean, when have smart guys on Wall Street been wrong about this stuff? (4)

So, in summary: Instead of buying ALL THE COMPANIES UNDER THE SUN for just THREE CENTS in the form of an index fund, let’s buy a lot of individual stocks (but nowhere near as many as the index) so we have the opportunity to buy XEROX when we sell IBM.

This is a lot of work. So how about we charge you something fair. Maybe something between 0.4% and 1.5 or so%? (5) Yes, yes, something between 10x and 50x the cost of that Vanguard fund. But you should pay that much more, because this is “Tax Smart!”

The Downsides of “Tax Smart” Investing

There’s a lot to unpack here. Some of the inefficiencies of this is obvious. Some are not.

1. You do not want to own just a subset of the market. This was the whole problem that John Bogle and Vanguard solved. This is why – in the history of Wall Street above – I call the “development” of Direct Indexing, a “(De)volution.” We really are going backwards.

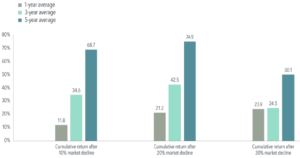

Let me put some meat on that bone to explain why this is not a good thing: did you know that just 4% of all stocks account for HALF of the stock market return over nearly the last 100 years?

Imagine Direct Indexing were around in the early 2000s. Under a Direct Indexing (Tax Smart) approach, you might have just owned Barnes & Noble and not Amazon.

I mean, Amazon.com just sold books when they first came out, right? I don’t know what it’s trading at today, but at one point Barnes & Noble stock dropped more than 99% from its high. And I don’t need to tell you how much Amazon stock has increased.

As John Bogle knew, you really should just own BOTH Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

2. The costs are much higher than investing in an index. If you are a financial firm on Wall Street, which would you rather sell? The index ETF that you can charge 0.03% for, or the one that you can charge 10x, 20x or more in fees? Follow the money. Just because the product is great for the sponsor, doesn’t mean it’s great for the investor. (See also, whole life insurance.)

3. The strategy eventually stops working if you stop putting in money. The stock market has always had a slow steady upward bias in price, if for no other reason than inflation. Over time, lots of investments will go up for this reason alone. And as they do, guess what: you no longer will have a loss to harvest! If you bought that publicly traded 8-track manufacturer based in Wisconsin for $0.43 in 1983, um…. You think you’re going to have a tax loss to harvest? The way I like to refer to it is your investments get “fossilized” over time.

4. Your portfolio becomes a complicated mess. After a few years of engaging in this strategy, you’ll have individual stock positions in all sorts of interesting companies. When you’re in your 80s, you may be asking yourself why you have shares of Borgwarner, Qorvo, and Jabil.

5. The value of those tax losses that you harvested is highly variable. Yes – all things being equal – I’d rather have a tax loss that I can use to offset gains than not. But a critical part of this analysis is having a good sense of exactly how valuable those tax losses are to you. Because to use them, you ultimately need to have a lot of taxable capital gains to offset. But are you planning on selling a lot of stocks anytime soon? If you’re in your 30s, 40s, 50s or even your 60s, you may still be in your “wealth accumulation mode” where you’re still just buying stocks. You’re not selling now! And yes, you can carry those losses forward to shelter future gains. But if that future is 20, 30, or 40 years from now (as it is for many of my clients), these current losses will be much smaller in the future on an inflation-adjusted basis. Great, your tax loss harvested $3.72 by selling your IBM stock. Your 2062 self will be thanking you for sheltering $3.72 of gain when a Starbucks Latte costs $45. Further, the truth is, a lot of people die with stock investments they made years and years ago. And these assets get transferred to their heirs with a step-up in basis, such that no capital gains tax is ever paid. All this is to say that the net benefit of the strategy is very difficult to calculate, and will be highly dependent on each person’s particular situation.

6. It can kind of trap you with a manager. Having a portfolio that is very complex (with lots of individual stock positions with various cost bases) I think cements you with a manager. I think you should always be free to leave your advisor if you don’t like working with them, and if you have a portfolio mess on your hands, you might reasonably feel trapped and captive, since you wouldn’t know what to do with it if you had to manage it on your own.

What’s the conclusion? Maybe you do decide to invest in this product. And I can’t tell you you’re wrong to do so as I don’t know your particular situation. But as they say, this is one situation where I think you really (really) need to consult with your (fee-only, fiduciary) advisor!